|

| Team handball |

Handball (also known as team handball, Olympic handball, European handball, or Borden ball[1]) is a team sport in which two teams of seven players each (six outfield players and a goalkeeper) pass a ball to throw it into the goal of the other team. A standard match consists of two periods of 30 minutes, and the team with the most goals scored wins.

Modern handball is usually played indoors, but outdoor variants exist in the forms of field handball and Czech handball (which were more common in the past) and beach handball (also called sandball).

The game is quite fast and includes body contact as the defenders try to stop the attackers from approaching the goal. Contact is only allowed when the defensive player is completely in front of the offensive player, i.e. between the offensive player and the goal. This is referred to as a player sandwich. Any contact from the side or especially from behind is considered dangerous and is usually met with penalties. When a defender successfully stops an attacking player, the play is stopped and restarted by the attacking team from the spot of the infraction or on the nine meter line. Unlike in basketball where players are allowed to commit only 5 fouls in a game (6 in the NBA), handball players are allowed an unlimited number of "faults", which are considered good defence and disruptive to the attacking team's rhythm.

Goals are scored quite frequently; usually both teams score at least 20 goals each, and it is not uncommon for both teams to score more than 30 goals. This was not true in the earliest history of the game, when the scores were more akin to that of ice hockey[clarification needed]. But, as offensive play has improved since the late 1980s, particularly the use of counterattacks (fast breaks) after a failed attack from the other team, goal scoring has increased.

Origins and development

|

| Team handball |

There are records of handball-like games in medieval France, and among the Inuit in Greenland, in the Middle Ages. By the 19th century, there existed similar games of håndbold from Denmark, házená in the Czech Republic, hádzaná in Slovakia, gandbol in Ukraine, torball in Germany, as well as versions in Uruguay.

The team handball game of today was formed by the end of the 19th century in northern Europe, primarily Denmark, Germany, Norway and Sweden. The first written set of team handball rules was published in 1906 by the Danish gym teacher, lieutenant and Olympic medalist Holger Nielsen from Ordrup grammar school north of Copenhagen. The modern set of rules was published on 29 October 1917 by Max Heiser, Karl Schelenz, and Erich Konigh from Germany. After 1919 these rules were improved by Karl Schelenz. The first international games were played under these rules, between Germany and Belgium for men in 1925 and between Germany and Austria for women in 1930. Therefore modern handball is generally seen as a game of German origins.

In 1926, the Congress of the International Amateur Athletics Federation nominated a committee to draw up international rules for field handball. The International Amateur Handball Federation was formed in 1928, and the International Handball Federation was formed in 1946.

Men's field handball was played at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. During the next several decades, indoor handball flourished and evolved in the Scandinavian countries. The sport re-emerged onto the world stage as team handball for the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. Women's team handball was added at the 1976 Summer Olympics. Due to its popularity in the region, the Eastern European countries that refined the event became the dominant force in the sport when it was reintroduced.

The International Handball Federation organized the men's world championship in 1938 and every 4 (sometimes 3) years from World War II to 1995. Since the 1995 world championship in Iceland, the competition has been every two years. The women's world championship has been played since 1957. The IHF also organizes women's and men's junior world championships. By July 2009, the IHF listed 166 member federations - approximately 795,000 teams and 19 million players.

Rules

The rules are a quoted in the IHF's Set of rules

Summary

The handball playing field is similar to an indoor soccer field. Two teams of seven players (six field players plus one goalkeeper) take the field and attempt to score points by putting the game ball into the opposing team's goal. In handling the ball, players are subject to the following restrictions:

After receiving the ball, players can pass, dribble (similar to a basketball dribble), or shoot the ball.

After receiving the ball, players can take up to three steps without dribbling. If players dribble, they may take an additional three steps.

Players that stop dribbling have three seconds to pass or shoot. They may take three additional steps during this time.

No players other than the defending goalkeeper are allowed within the goal line (within 6 meters of the goal). Goalkeepers are allowed outside this line.

|

| Team handball |

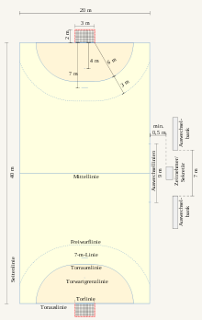

Playing field

Handball is played on a court 40 by 20 metres (130 × 66 ft), with a goal in the center of each end. The goals are surrounded by a near-semicircular area, called the zone or the crease, defined by a line six meters from the goal. A dashed near-semicircular line nine meters from the goal marks the free-throw line. Each line on the court is part of the area it encompasses. This implies that the middle line belongs to both halves at the same time.

Goals

The goals are surrounded by the crease. This area is delineated by two quarter circles with a radius of six meters around the far corners of each goal post and a connecting line parallel to the goal line. Only the defending goalkeeper is allowed inside this zone. However, the court players may catch and touch the ball in the air within it as long as the player starts his jump outside the zone and releases the ball before he lands (landing inside the perimeter is allowed in this case).

If a player contacts the ground inside the goal perimeter he must take the most direct path out of it. However, should a player cross the zone in an attempt to gain an advantage (e.g. better position) his team cedes the ball. Similarly, violation of the zone by a defending player is only penalized if he does so to gain an advantage in defending.

|

| Team handball |

|

| Team handball |

Substitution area

Outside of one long edge of the playing field to both sides of the middle line are the substitution areas for each team. The areas usually contain the benches as seating opportunities. Team officials, substitutes and suspended players must wait within this area. The area always lies to the same side as the team's own goal. During half-time substitution areas are swapped. Any player entering or leaving the play must cross the substitution line which is part of the side line and extends 4.5 meters from the middle line to the team's side.

Duration

A standard match for all teams of 16 and older has two periods of 30 minutes with a 15 minute half-time. Teams switch sides of the court at halftime, as well as benches. For youths the length of the halves is reduced - 25 minutes at ages 12 to 16 and 20 minutes at ages 8 to 12, though national federations of some countries may differ in their implementation from the official guidelines.

If a decision must be reached in a particular match (e.g. in a tournament) and it ends in a draw after regular time, there are at maximum two overtimes of 2 x 5 minutes with a 1 minute break each. Should these not decide the game either, the winning team is determined in a penalty shootout (best-of-5 rounds; if still tied, extra rounds afterwards until won by one team).

The referees may call timeout according to their sole discretion; typical reasons are injuries, suspensions or court cleaning. Penalty throws should only trigger a timeout for lengthy delays as a change of the goalkeeper.

Each team may call one team timeout (TTO) per period which lasts one minute. This right may only be invoked by team in ball possession. To do so, the representative of the team lays a green card marked with a black "T" on the desk of the timekeeper. The timekeeper then immediately interrupts the game by sounding an acoustic signal and stops the time.

Referees

A handball match is led by two equal referees, namely the goal line referee and the court referee. Some national bodies allow games with only a single referee in special cases like illness on short notice. Should the referees disagree on any occasion, a decision is made on mutual agreement during a short timeout, or, in case of punishments, the more severe of the two comes into effect. The referees are obliged to make their decisions "on the basis of their observations of facts". Their judgements are final and can only be appealed against if not in compliance with the rules.

The referees position themselves in such a way that the team players are confined between them. They stand diagonally aligned so that each can observe one side line. Depending on their positions one is called field referee and the other goal referee. These positions automatically switch on ball turnover. They physically exchange their positions approximately every 10 minutes (long exchange) and change sides every 5 minutes (short exchange).

The IHF defines 18 hand signals for quick visual communication with players and officials. The signal for warning or disqualification is accompanied by a yellow or red card,[4] respectively. The referees also use whistle blows to indicate infractions or restart the play.

The referees are supported by a scorekeeper and a timekeeper who attend to formal things like keeping track of goals and suspensions or starting and stopping the clock, respectively. They also have an eye on the benches and notify the referees on substitution errors. Their desk is located in between both substitutions areas.

Team players, substitutes and officials

Each team consists of 7 players on court and 7 substitute players on the bench. One player on the court must be the designated goalkeeper differing in his or her clothing from the rest of the field players. Substitution of players can be done in any number and at any time during game play. An exchange takes place over the substitution line. A prior notification of the referees is not necessary.

Some national bodies as the Deutscher Handball Bund (DHB, "German Handball Federation") allow substitution in junior teams only when in ball possession or during timeouts. This restriction is intended to prevent early specialization of players to offense or defense.

Field players

Field players are allowed to touch the ball with any part of their bodies above and including the knee. As in several other team sports, a distinction is made between catching and dribbling. A player who is in possession of the ball may stand stationary for only three seconds and may only take three steps. They must then either shoot, pass or dribble the ball. At any time taking more than three steps is considered travelling and results in a turnover. A player may dribble as many times as he wants (though since passing is faster it is the preferred method of attack) as long as during each dribble his hand contacts only the top of the ball. Therefore carrying is completely prohibited, and results in a turnover. After the dribble is picked up, the player has the right to another three seconds or three steps. The ball must then be passed or shot as further holding or dribbling will result in a "double dribble" turnover and a free throw for the other team. Other offensive infractions that result in a turnover include, charging, setting an illegal screen, or carrying the ball into the six meter zone.

|

| Team handball |

Goalkeeper

Only the goalkeeper is allowed to move freely within the goal perimeter, although he may not cross the goal perimeter line while carrying or dribbling the ball. Within the zone, he is allowed to touch the ball with all parts of his body including his feet. The goalkeeper may participate in the normal play of his team mates. As he is then considered as normal field player, he is typically substituted for a regular field player if his team uses this scheme to outnumber the defending players. As this player becomes the designated goalkeeper on the court, he must wear some vest or bib to identify himself as such.

If the goalkeeper deflects the ball over the outer goal line, his team stays in possession of the ball in contrast to other sports like football. The goalkeeper resumes the play with a throw from within the zone ("goalkeeper throw"). Passing to your own goalkeeper results in a turnover. Throwing the ball against the head of the goalkeeper when he is not moving is to be punished by disqualification ("red card").

Team officials

Each team is allowed to have a maximum of four team officials seated on the benches. An official is anybody who is neither player nor substitute. One official must be the designated representative who is usually the team manager. The representative may call team timeout once every period and may address scorekeeper, timekeeper and referees. Other officials typically include physicians or managers. Neither official is allowed to enter the playing court without permission of the referees.

Ball

The ball is spherical and must either be made of leather or a synthetic material. It is not allowed to have a shiny or slippery surface. As it is intended to be operated by a single hand, the official sizes vary depending on age and gender of the participating teams.

Size Used by Circumference (in cm) Weight (in g)

III Men and male youth older than 16 58–60 425–475

II Women, male youth older than 12 and female youth older than 14 54–56 325–375

I Youth older than 8 50–52 290–330

Resin product used to improve ball handling.

Though not officially regulated, the ball is usually resinated. The resin improves the ability of the players to manipulate the ball with a single hand like spinning trick shots. Some indoor arenas prohibit the usage of resin since many products leave sticky stains on the floor.

Awarded throws

The referees may award a special throw to a team. This usually happens after certain events like scored goals, off-court balls, turnovers, timeouts, etc. All of these special throws require the thrower to obtain a certain position and pose restrictions on the positions of all other players. Sometimes the execution must wait for a whistle blow by the referee.

Throw-off

A throw-off takes place from the center of the court. The thrower must touch the middle line with one foot and all the other offensive players must stay in their half until the referee restarts the game. The defending players must keep a distance of at least three meters to the thrower. A throw-off occurs at the beginning of each period and after the opposing team scores a goal. It must be cleared by the referees.

Modern Handball introduced the "fast throw-off" concept, i. e. the play will be immediately restarted by the referees as soon as the executing team fulfilles its requirements. Many teams leverage this rule to score easy goals before the opposition has time to form a stable defense line.

Throw-in

The team which did not touch the ball last is awarded a throw-in when the ball fully crosses the side line or touches the ceiling. If the ball crosses the outer goal line, a throw-in is only awarded if the defending field players touched the balls last. Execution requires the thrower to place one foot on the nearest outer line to the cause. All defending players must keep a distance of three meters. However, they are allowed to stand immediately outside their own goal area even when the distance is less.

Goalkeeper-throw

If ball crosses the outer goal line without interference from the defending team or when deflected by their goalkeeper, a goalkeeper-throw is awarded to the defending team. This is the most common turnover. The goalkeeper resumes the play with a throw from anywhere within his goal area.

Free-throw

A free-throw restarts the play after an interruption by the referees. It takes places from the spot where the interruption was caused as long as this spot is outside of the free-throw line of the opposing team. In the latter case the throw is deferred to the nearest spot on the free-throw line. Free-throws are the equivalent to free-kicks in association football. The thrower may take a direct attempt for a goal which is, however, not feasible if the defending team organized a defense.

|

| Team handball |

7-meter throw

A 7-meter throw is awarded when a clear chance of scoring is illegally prevented anywhere on the court by an opposing team player, official or spectator. It is also awarded when the referees interrupted a legitimate scoring chance for any reason. The thrower steps with one foot behind the 7-meter line with only the defending goalkeeper between him and the goal. The goalkeeper must keep a distance of three meters which is marked by a short tick on the floor. All other players must remain behind the free-throw line until execution. The thrower must await the whistle blow of the referee. A 7-meter throw is the equivalent to a penalty kick in association football, it is, however, far more common and typically occurs several times in a single game.

Penalties

Penalties are given to players, in progressive format, for fouls that require more punishment than just a free-throw. "Actions" directed mainly at the opponent and not the ball (such as reaching around, holding, pushing, hitting, tripping, or jumping into opponent) as well as contact from the side or from behind a player are all considered illegal and subject to penalty. Any infraction that prevents a clear scoring opportunity will result in a seven-meter penalty shot.

Typically the referee will give a warning yellow card for an illegal action, but if the contact was particularly dangerous the referee can forego the warning for an immediate two-minute suspension. A player can only get one warning before receiving a two minute suspension. One player is only permitted two 2-minute suspensions; third time he/she will be shown the red card.

A red card results in an ejection from the game and a two minute penalty for the team. A player may receive a red card directly for particularly rough penalties. For instance any contact from behind during a fast break is now being treated with a red card. A red carded player has to leave the playing area completely. A player who is disqualified may be substituted with another player after the two minute penalty is served. A Coach/Official can also be penalized progressively. Any coach/official who receives a 2-minute suspension will have to pull out one of his players for two minutes - note: the player is not the one punished and can be substituted in again, because the main penalty is the team playing with a man less than the other.

After having lost the ball during an attack, the ball has to be laid down quickly or else the player not following this rule will face a 2-minute suspension. Also gesticulating or verbally questioning the referee's order, as well as arguing with the officials decisions, will normally result in a 2-minute suspension. If it is done in a very provocative way, a player can be given a double 2-minute suspension if he/she does not walk straight off the field to the bench after being given a suspension, or if the referee deems the tempo deliberately slow. Illegal substitution, any substitution that does not take place in the specified substitution area or where the entering player enters before the exiting player exits is also punishable with a 2 minute suspension.

Formations

Players are typically referred to by the position they are playing. The positions are always denoted from the view of the respective goalkeeper, so that a defender on the right opposes an attacker on the left. However, not all of the following positions may be occupied depending on the formation or potential suspensions.

Offense

Left and right wingman. These typically excel at ball control and wide jumps from the outside of the goal perimeter to get into a better shooting angle at the goal. Teams usually try to occupy the left position with a right-handed player and vice versa.

Left and right backcourt. Goal attempts by these players are typically made by jumping high and shooting over the defenders. Thus, it is usually advantageous to have tall players for these positions.

Center backcourt. A player with experience is preferred on this position who acts as playmaker and the handball equivalent of a basketball point guard.

Pivot (left and right, if applicable). This player tends to intermingle with the defense, setting picks and attempting to disrupt the defense formation. This positions requires the least jumping skills but ball control and physical strength are an advantage.

Defense

Far left and far right. The opponents of the wingmen.

Half left and half right. The opponents of the left and right backcourts.

Back center (left and right). Opponent of the pivot.

Front center. Opponent of the center backcourt, may also be set against another specific backcourt player.

Offensive play

Attacks are played with all field players on the side of the defenders. Depending on the speed of the attack, one distinguishes between three attack waves with a decreasing chance of success:

First Wave

First wave attacks are characterized by the absence of defending players around their goal perimeter. The chance of success is very high, as the throwing player is unhindered in his scoring attempt. Such attacks typically occur after an intercepted pass or a steal and if the defending team can switch fast to offense. The far left/far right will usually try to run the attack as they are not as tightly bound in the defense. On a turnover, they immediately sprint forward and receive the ball halfway to the other goal. Thus, these positions are commonly held by quick players.[citation needed]

Second Wave

If the first wave is not successful and some defending players gained their positions around the zone, the second wave comes into play: The remaining players advance with quick passes to locally outnumber the retreating defenders. If one player manages to step up to the perimeter or catches the ball at this spot he becomes unstoppable by legal defensive means. From this position the chance of success is naturally very high. Second wave attacks became much more important with the "fast throw-off" rule.[citation needed]

Third Wave

The time during which the second wave may be successful is very short, as then the defenders closed the gaps around the zone. In the third wave, the attackers use standardized attack patterns usually involving crossing and passing between the back court players who either try to pass the ball through a gap to their pivot, take a jumping shot from the backcourt at the goal, or lure the defense away from a wingman.[citation needed]

The third wave evolves into the normal offensive play when all defenders reach not only the zone but gain their accustomed positions. Some teams then substitute specialized offense players. However, this implies that these players must play in the defense should the opposing team be able to switch quickly to offense. The latter is another benefit for fast playing teams.[citation needed]

If the attacking team does not make sufficient progress (eventually releasing a shot on goal), the referees can call passive play (since about 1995, the referee gives a passive warning some time before the actual call by holding one hand up in the air, signaling that the attacking team should release a shot soon), turning control over to the other team. A shot on goal or an infringement leading to a yellow card or two minute penalty will mark the start of a new attack, causing the hand to be taken down, but a shot blocked by the defense or a normal free throw will not. If it were not for this rule, it would be easy for an attacking team to stall the game indefinitely, as it is difficult to intercept a pass without at the same time conceding dangerous openings towards the goal.[citation needed]

Defensive play

The usual formations of the defense are 6-0, when all the defense players line up between the 6 meter and 9 meter lines to form a wall; the 5-1, when one of the players cruises outside the 9 meter perimeter, usually targeting the center forwards while the other 5 line up on the six meter line; and the lesser common 4-2 when there are two such defenders out front. Very fast teams will also try a 3-3 formation which is close to a switching man-to-man style. The formations vary greatly from country to country and reflect each country's style of play. 6-0 is sometimes known as "flat defense", and all other formations are usually called "offensive defense".[citation needed]

Organization

Handball teams are usually organized as clubs. On a national level, the clubs are associated in federations which organize matches in leagues and tournaments.

International bodies

The administrative and controlling body for international Handball is the International Handball Federation (IHF). The federation organizes world championships, separate for men and women, held in uneven years. The final round is hosted in one of its member states. Current title holders are France (men) and Russia (women).

National competitions

Macedonia: Macedonian First League of Handball

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Handball Championship of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Croatia: Croatian First League of Handball

Czech : Zubr extraliga

Denmark: GuldBageren Ligaen, Jack & Jones Ligaen

France: Ligue Nationale de Handball

Germany: Handball-Bundesliga

Greece: Greek Men's handball championship

Hungary: Nemzeti Bajnokság I (men), Nemzeti Bajnokság I (women)

Iceland: N1 deildin

Montenegro: First League (men), First League (women), Second League (women)

Poland: Polish Ekstraklasa Men's Handball League, Polish Ekstraklasa Women's Handball League

Portugal: Liga Portuguesa de Andebol, Divisão de Elite

Romania: Liga Naţională (men), Liga Naţională (women)

Scotland: Scottish Handball League

Serbia: Serbian First League of Handball

Slovakia: Slovenská hadzanárska extraliga

Slovenia: Slovenian First League of Handball, Handball Cup of Slovenia

Spain: Liga ASOBAL, División de Plata de Balonmano

Sweden: Elitserien

Turkey: Turkish Handball Super League

United States: U.S. intercollegiate handball championships

Commemorative coins

Handball events have been selected as a main motif in numerous collectors' coins. One of the recent samples is the €10 Greek Handball commemorative coin, minted in 2003 to commemorate the 2004 Summer Olympics. On the coin, the modern athlete directs the ball in his hands towards his target, while in the background the ancient athlete is just about to throw a ball, in a game known as cheirosphaira, in a representation taken from a black-figure pottery vase of the Archaic period.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)